The tech-ephant in the room: Unpacking implicit bias in the prescription of diabetes tech

By Alicia Shelly, MD, FACP

6 min read

Everyone has implicit biases—unconscious assumptions that we accrue from our experiences and our backgrounds.1 Yes, even us doctors.

I think it’s more important than ever to have conversations about this topic, and I often do. Based on my talks with other providers, these biases are acknowledged, and I genuinely believe that most physicians mean well. But acknowledging our biases isn’t enough. We have an obligation to take concrete steps to confront and combat our biases. If we don’t, these assumptions can obstruct the care we provide.1

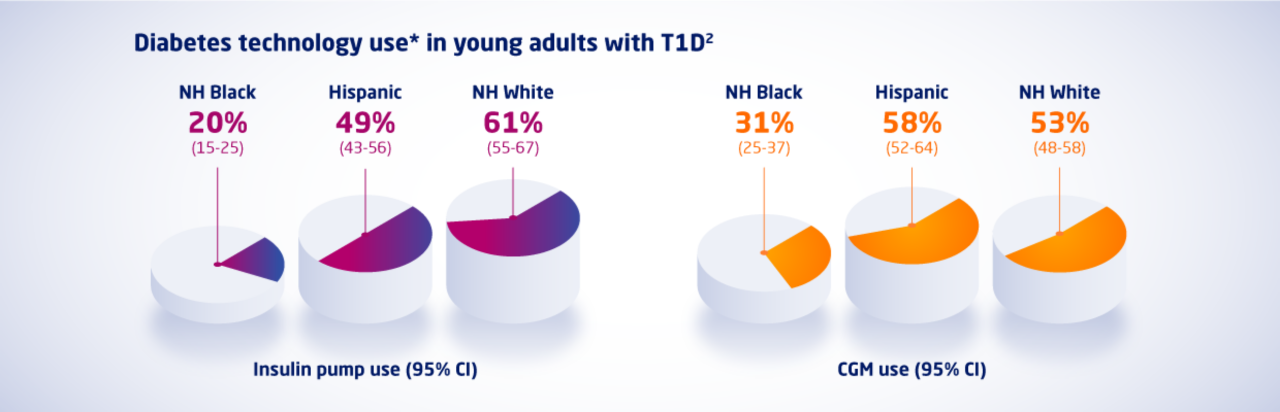

Let’s consider an example of potential bias contributing to inequity in the world of diabetes tech. There’s a proven gap in the usage of CGMs among non-Hispanic Black (NHB), Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white (NHW) young adults with type 1 diabetes. This gap exists in spite of the demonstrable A1C benefits that CGMs can have for many people living with diabetes, both for those taking insulin and those who do not. A similar gap exists in the use of insulin pumps.2,3

Based on a sample of 300 young adult participants with T1D (100 NH white, 97 NH Black, 103 Hispanic). Results are fully adjusted, which refers to the usage rate for each device if all factors were the same for each group. Adjustment factors include: age, sex, study site, insurance, educational level, Hollingshead Four Factor Index score (self-reported measure of social status based on marital status, employment status, educational attainment, and occupation), neighborhood poverty level, health literacy, Self-Care Inventory (SCI) total score, diabetes numeracy, self-reported blood glucose monitoring frequency (SCI single-item score), self-reported clinic attendance (SCI single-item score), and pediatric versus adult care site.

*Current insulin pump and CGM use in past year

In examining these gaps, we should recognize that implicit bias is one of many factors that may contribute to inequities in insulin pump and CGM use. We can’t take an oversimplified view of this study and assume that we as providers are entirely responsible. After all, diabetes tech is still prohibitively expensive for many people, regardless of insurance.3

On the other hand, it is also true that patients from communities with lower device usage rates report feeling left out of the decision-making process for their care.3 Young adults like those involved in the above study are also in a critical period as they transition from pediatric to adult care. The patient-provider relationship might be a deciding factor in the continued use and adoption of devices for populations with low usage rates.2

If there’s one thing I’ve realized about prescribing tech to people with diabetes, it’s that equity doesn’t begin with access. Instead, I think it starts with educating people and making sure their feedback is considered.

It’s here that we might be able to make a difference with an approach to patient care that is equitable, yet individualized. Personally, I use a 3-step approach that helps me to check my biases and help ensure that I am treating each patient equitably. I call it ASK:

Assume you are assuming things

Start by listening

Know that you don’t know everything

Let’s walk through this approach in context with my experiences as a primary care physician.

1. Assume you are assuming things

It’s important to slow down and be intentional about how I prepare for an appointment, and that starts with recognizing my own biases and setting them aside. By making the assumption that I am assuming things about each patient, it’s easier for me to spot those potential biases and root them out.

For example, I had a visit with an older patient with type 2 diabetes. He was diagnosed long enough ago that I could have assumed he wasn’t interested in tech or might not have wanted to change his routine by adding a new device. A reflexive assumption like that could be true, but if it’s not, I may have missed an opportunity to help a patient with an appropriate piece of tech.

The next time a thought about a patient makes you hesitate, challenge that thought—is it based on an assumption?

There are resources online that can facilitate the process of recognizing one’s biases. I’ve found success with the free tests from Project Implicit. Their assessments cover a range of topics, which is critical—biases come in many forms.4

When I have a better understanding of areas where I might be biased, I can stop and say, “Hold on, let’s walk that back.” I don’t limit myself to doing this just before a visit, either. I like to reflect right after a visit on how conversations went with a patient, while my thoughts are fresh, so I know where I can do better next time, or if I may want to follow up.

2. Start by listening

Treating everyone equitably starts with giving all patients an opportunity to feel heard. I always want to start by giving people a chance to open up so I can hear what they have to say.

Let’s say a patient comes to me and I see that they’re receiving government assistance. I also see that their blood glucose is uncontrolled. Already, there are some conclusions I could jump to about the way they manage their diabetes and whether tech would be appropriate for them.

Instead, I ask open-ended questions to better understand the patient’s experience.

- “How do you feel about your recent blood sugar levels?”

- “How have you been keeping up with your dosing log?”

- “How would you feel about trying a device that may help you track your insulin doses?”

When I give the patient the floor, I’m giving them a chance to let me know what’s going on in their lives. Hearing directly from them lets me offer individualized care to the person in front of me rather than a potentially biased response to information in a file.

By making the assumption that I am assuming things about each patient, it’s easier for me to spot those potential biases and root them out.

3. Know that you don’t know everything

As primary care physicians, we know a lot. It’s our job. But a downside of needing to have such a breadth of knowledge on so many conditions and treatments is that it can be hard to keep up with the latest developments in every specialty.

It used to be that patients who were on Medicare had a high barrier to entry for a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) prescription. For years, I practiced knowing that this population needed to be checking their blood sugar 4 times a day, that they needed to be taking a long-acting insulin, and so on, otherwise they didn’t qualify for the tech.

Now, the standards have changed—more people with type 2 diabetes and those who aren’t taking insulin are eligible for these devices,5,6 and that has changed how I practice. I bring this up because providers with more experience may be less likely to prescribe tech to people with diabetes based on assumptions they have about insurance.1

I think it’s important to be flexible and willing to understand that the things we know can change. That means staying on top of current standards by talking to our colleagues, attending conferences, and participating in continuing medical education.

It could also mean taking time to research things our patients bring up. In a world of commercialized health care, it’s not uncommon for a patient to mention a new medication or a new technology that I’m not super familiar with. In those situations, I’ve found it’s worth taking the time to check on it just in case it could make a difference. It takes a lot of humility and self-awareness, but ultimately I believe it helps me to be a better provider to my patients.

During a good conversation with your patients, expect to listen as much as you talk, if not more.

If you made it here and through the detailed description of each step of my approach, I’m glad. But really, the most important takeaway is in the name of the approach itself: ASK. Don’t assume, just ask, and listen to what your patients tell you.

For every 100 times I ask an “obvious” question and get an answer I was expecting, there are a handful of times that I don’t, and that may make a big difference in what I decide for the patient’s treatment plan.

Tech-up Follow-ups

- Set aside time to reflect on biases you might hold. Consider patient visits you’ve had in the past month and whether you demonstrated any assumptions while practicing.

- Prepare 2 to 3 open-ended questions that you can ask every patient you see with the goal of encouraging them to open up and be honest about their health.

- Make plans to participate in continuing medical education about provider bias. If there aren’t any opportunities close at hand, reach out to a colleague and ask if they would be willing to compare notes on current best practices for patient-centered care.

Alicia Shelly, MD, FACP

Douglasville, Georgia

Dr Shelly is a primary care provider who regularly sees patients with diabetes. She is a board-certified internal medicine physician at Wellstar Primary Care in Douglasville, Georgia.

Alicia Shelly received a fee from Novo Nordisk for her participation.

–— Recommended for you –—

References

- Addala A, Hanes S, Naranjo D, Maahs DM, Hood KK. Provider implicit bias impacts pediatric type 1 diabetes technology recommendations in the United States: findings from The Gatekeeper Study. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2021;15(5):1027-1033. doi:10.1177/19322968211006476

- Agarwal S, Schechter C, Gonzalez J, Long JA. Racial-ethnic disparities in diabetes technology use among young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021;23(4):306-313. doi:10.1089/dia.2020.0338

- Agarwal S, Simmonds I, Myers AK. The use of diabetes technology to address inequity in health outcomes: limitations and opportunities. Curr Diab Rep. 2022;22(7):275-281. doi:10.1007/s11892-022-01470-3

- Project Implicit. Accessed August 2023. https://www.projectimplicit.net/

- American Diabetes Association. New medicare coverage requirements make CGMs more accessible. Diabetes.org. Accessed August 2023. https://diabetes.org/tools-support/devices-technology/cgm-medicare-coverage-requirement-change-accessibility

- Moreau D. Final medicare continuous glucose monitor (CGM) policy goes into effect April 16. Danatech Diabetes Technology @ ADCES. April 7, 2023. Accessed August 2023. https://www.diabeteseducator.org/danatech/latest-news/danatech-latest-news/2023/04/07/final-medicare-continuous-glucose-monitor-(cgm)-policy-goes-into-effect-april-16th

The Diabetes Tech-upTM Podcast

Join our expert cohosts for a series of discussions about how they’re integrating diabetes tech with patient-centered care to help optimize diabetes management.

The Mission of Diabetes Tech-upTM

Diabetes Tech-upTM is sponsored by Novo Nordisk, a global leader in diabetes. We believe that adoption of innovative technologies can help appropriate patients better manage diabetes. Our goal is to provide information to help health care professionals on the front line of diabetes care strengthen their understanding of diabetes technologies and implement them where they can have the greatest impact.

Share: